Music & Dharma

From its origins, music has been essential to Buddhist practice. From Tibetan chants to Zen sutra recitations, from Theravada devotional traditions to the spontaneous dohas of mahasiddhas, the Dharma has always recognized music's unique power to touch the human heart in ways that transcend rational understanding.

As Buddhist teachings traveled from India to Tibet, China, Japan, and beyond, they naturally expressed themselves through each culture's musical traditions. Sanskrit mantras acquired Tibetan melodies. Chinese sutras developed their own tonal cadences. Each tradition understood music not as mere ornament, but a direct vehicle for awakening devotion, concentration, and insight.

The Buddha's own awakening path was illuminated by music. When Siddhartha Gautama had nearly destroyed himself through extreme asceticism, it was the sound of a vina player teaching his student that provided the insight that changed everything: "If the strings are too tight, they will break. If they are too loose, they will not play. The middle way produces the most beautiful music." This musical metaphor became the foundation of the Buddha's Middle Path—the recognition that liberation comes not through extremes but through skillful balance.

Throughout the sutras, music appears as both metaphor and method. In the Lotus Sutra, celestial beings offer music to the Buddha. The traditional offerings to enlightened beings include water, flowers, incense, light, perfume—and music. Sound itself is recognized as one of the supreme offerings, capable of reaching the depths of consciousness in ways material gifts cannot.

The Gandharvas, celestial musicians in Buddhist cosmology, embody the understanding that music is not entertainment but a bridge between realms, a vehicle for touching what lies beyond ordinary perception.

Their music doesn't just please the ear—it awakens wisdom, stirs devotion, and reminds practitioners of the harmony underlying all phenomena.

Their music isn't just for entertainment; it is often described as a form of spiritual praise or an offering that accompanies the sermons of the Buddha.

Gandharvas are the master musicians of the heavens, and they are typically depicted playing a wide variety of classical Indian instruments

The Sublime Melody of Buddha's Voice

The metaphor of Brahma’s voice (Brahmaghosa) serves as the ultimate aesthetic and spiritual standard for the speech of the Buddha and the Enlightened Ones, characterized by its "eight qualities" of being deep, resonant, clear, and harmonious. It is one of a Buddha’s thirty-two features. The voice of the Buddha is said to be pure and to reach all the worlds in the ten directions. This is symbolic of the power of a Buddha’s voice to delight those who hear it, deeply touch people’s hearts, and inspire a sense of reverence.

In a myriad of Buddhist prayers and dharanis, the Buddha’s voice is likened to the sound of a celestial Gandharva or the majestic call of the Kalapinka bird, possessing a melodic power that reaches across world systems without losing its clarity.

This divine resonance is not merely a matter of volume, but of perfect equilibrium; just as the strings of a vina must be tuned to the Middle Way to produce a true note, Brahma's voice represents a sound free from the "noise" of worldly attachment or the "silence" of nihilism.

When practitioners invoke this metaphor in prayer, they are calling upon the capacity of Dharma to penetrate the heart instantly, transforming the listener’s consciousness through a vibration that is both authoritative and profoundly soothing.

The 8 Traditional Qualities of Buddha's Voice

According to the Sumaṅgalavilāsinī (the commentary on the Long Discourses of the Buddha), this sound is the ultimate aesthetic standard because it is:

Fluent (Vissaṭṭha) – Smooth and effortless.

Intelligible (Viññeyya) – Easy for anyone to understand.

Sweet (Mañju) – Pleasant and lovely to the ear.

Audible (Savanīya) – Reaches everyone in the assembly clearly.

Continuous (Bindu) – Without unskillful breaks or pauses.

Distinct (Avisārī) – No blurring of words or meanings.

Deep (Gambhīra) – Resonant and authoritative.

Resonant (Ninnādī) – Vibrant, like the ring of a golden bell.

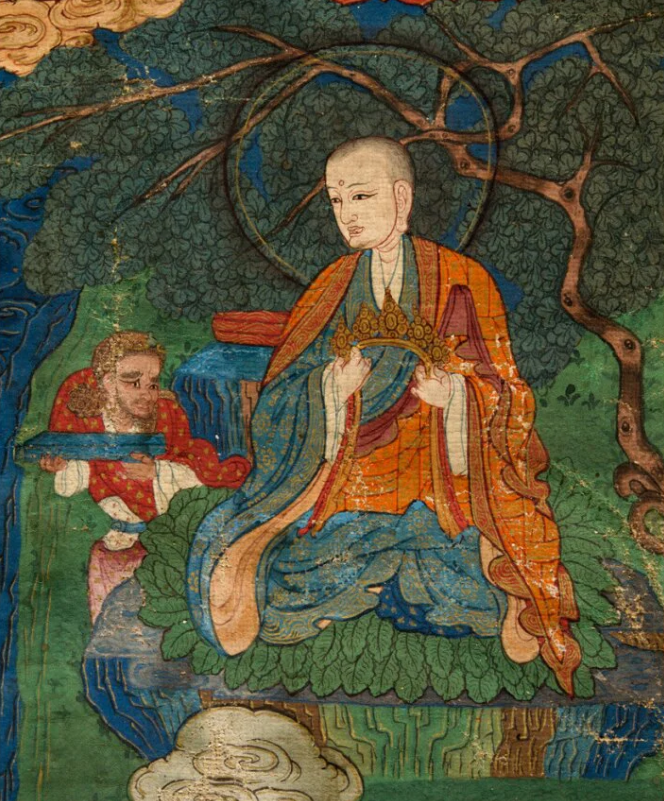

Thangka of Buddha Shakyamuni preaching the Dharma

Eastern Tibet, 16th or 17th century

From the collection of the Museum of Archaeology

and Anthropology, Cambridge

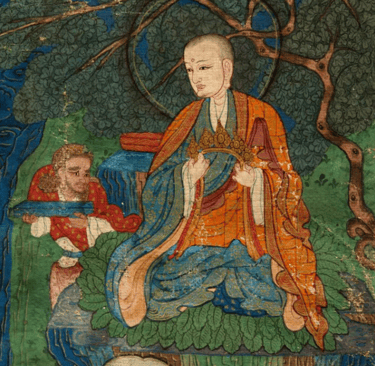

Indra offering the conch shell symbolizes the powerful and far-reaching sound of the Dharma

Image from enlightenmentthangka.com

Indra’s Offering to the Buddha: The Conch Shell

Right after Buddha attained enlightenment under the Bodhi Tree, Indra, the king of the gods and guardian of the spiritual world, presented a beautifully spiraled white conch shell to the Buddha. With a respectful bow, he said:

"O Enlightened One, may your voice, like this conch, resound far and wide, awakening those engulfed in darkness."

The conch shell symbolizes the powerful and far-reaching sound of the Dharma. Its spiral shape represents continuity and harmony, while its sound is believed to rouse beings from their spiritual slumber. Indra’s gesture emphasized the importance of spreading the Buddha’s teachings across the universe.

The offering of the white conch shell by Indra serves as a vital transition from the Buddha's internal realization to his external mission of teaching. While Brahma requested the turn of the Wheel, Indra provided the instrument of its proclamation, symbolizing the sovereignty and authority of the Dharma over all realms of existence. The conch, known as the Sankha, is unique because its sound is said to travel in all directions simultaneously, echoing the "Lion’s Roar" of the Buddha that penetrates the "spiritual slumber" of ignorance. By presenting this gift, Indra acknowledges that the truth discovered under the Bodhi tree is not a silent treasure to be guarded, but a resonant force intended to "awaken those engulfed in darkness." This moment marks the birth of the Buddhist oral tradition, ensuring that the Middle Way would not remain a solitary insight, but would vibrate through the air of Sarnath and eventually across the entire universe.

In Buddhism, the Music Offering Goddess is an active participant in a divine assembly, acting as a bridge between the physical and the enlightened mind through sound.

Why contemporary music as a medium for sharing the Dharma?

Alaya SoundLab honors the sacred role of music in the Dharma by bringing genuine Buddhist teachings into the sonic languages of our time, allowing the Dharma to continue its journey through new musical territories, reaching contemporary hearts with the same depth that has always characterized these timeless teachings.

The primary reason to bring Dharma into comtemporary music is very simple: like many people, you likely still know by heart dozens or hundreds—In my case, perhaps thousands—of song lyrics from your teenage years. Songs I haven't heard in decades, I can still sing word-for-word. Yet I know by heart only a handful of short Buddhist prayers, despite years of constant practice and study.

Now something revealing: in the process of creating Dharma music for fun, setting teachings I translated or read countless time to music, I've already memorized more Buddhist texts than in my entire life of just reading them. The difference is dramatic and immediate.

This isn't just my experience—it's neuroscience. Research shows that music activates multiple brain regions simultaneously: the auditory cortex processes sound, the motor cortex responds to rhythm, the limbic system adds emotion, and the hippocampus encodes memory. This multi-sensory engagement creates what researchers call "elaborative encoding"—our brains form multiple pathways to the same information, making it far easier to recall.

Studies have found that musical memory often remains intact even in advanced Alzheimer's patients who've lost most other memories. The combination of melody, rhythm, and emotion creates such powerful neural connections that information encoded through music becomes nearly permanent.

This is why you can instantly recall lyrics from songs you haven't heard in twenty years, but struggle to remember what you read this morning.

Music doesn't just carry information—it embeds it.

Countless people work the same way. We're not lazy or undisciplined—we're simply responding to how our brains are actually wired. If profound Buddhist teachings can reach us through the same neural pathways that permanently encoded our favorite songs, why wouldn't we use that? Why should Dharma be limited to the learning style that works for scholars, when music offers a gateway that works for so many more?

Music has always been humanity's bridge to the sacred—what we're doing with Alaya Sounds isn't innovation, but restoration. Anthropological evidence suggests that music predates language itself, with our earliest ancestors using rhythm, chant, and melody primarily for ritual purposes. Archaeological findings at sites like the Hohle Fels cave in Germany reveal 40,000-year-old bone flutes likely used in shamanic ceremonies, while ethnomusicological research across cultures—from the trance-inducing drumming of African spiritual traditions to the devotional ragas of India—demonstrates that music's original function was never entertainment, but communion with something beyond the ordinary. Aboriginal Australians used the didgeridoo in Dreamtime ceremonies for at least 1,500 years, Native American tribes employed song for vision quests and healing, and ancient Sumerians composed hymns to their deities on clay tablets. Even Pythagoras understood music as mathematical harmony reflecting cosmic order, a tool for aligning the soul with universal truth.

What modern culture has largely forgotten—and what Buddhist chanting, kirtan, gospel, and Sufi qawwali never lost—is that music is fundamentally a spiritual technology. By setting Dharma teachings to contemporary musical forms, we're not corrupting tradition; we're reclaiming music's ancient purpose, using modern tools and modern genres to do what music has always done best: open and connect our hearts and minds to truths larger than ourselves.